Clean Power 2030 is a dangerous fantasy

British energy policy is in the grip of wishful thinking, when hard-headed analysis is desperately needed.

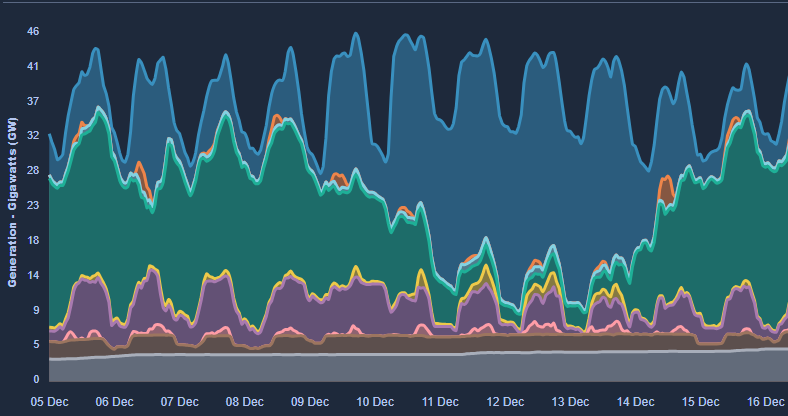

We might one day look back at December 2024 as a turning point in European energy policy. A multi-day lull in wind and solar power affected much of north-west Europe, combined with very low solar output: what the Germans call a dunkelflaute. It wasn’t so much that the weather was exceptional. But this time power prices spiked by up to 20 times across a wide area, in some cases reaching levels even higher than during the gas price surge of 2022 sparked by the Ukraine war. Even countries like Norway and Sweden, that generally manage to maintain lower electricity prices through plentiful hydro, were also affected due to increased interconnection between national markets.

The power price spike triggered immediate alarm, for example this from German commodities trader Alexander Stahel:

In Norway at least, it also caused a strong political reaction, with energy minister Terje Aaslund calling it an “absolutely shit situation”, and the government suggesting it would think again before approving any more electricity interconnection with other European countries. In Germany, the spike increased the political spotlight on the wisdom of the country’s exit from nuclear power.

Possibly the only place in north-west Europe where there was little comment was the UK, despite the fact that wind power output crashed here too, while solar generation was virtually non-existent.

Ironically, at this very moment, political attention focused instead on the Government’s Clean Power 2030 action plan for making the British system almost entirely reliant on wind and solar in just the next five years, published on 13 December.

In practical terms, Clean Power 2030 is mainly about actions to unclog the planning system for new energy infrastructure, change the way new projects are prioritised, and increase the size of auctions for new renewable energy projects. And the Government waxed lyrical when describing all the good things this will supposedly deliver:

“Working people will benefit from a new era of clean electricity, as the government today unveils the most ambitious reforms to the country’s energy system in a generation, to make Britain energy secure, protect households from energy price spikes, reindustrialise the country with thousands of skilled jobs, and tackle the climate crisis.”

I fear that this is a dangerous fantasy, written by people who believe that political will can overcome both economics and physics. Many critics focus their blame on energy secretary, Ed Miliband. But in fact the vision is supported also by a mass of officials at the Department for Energy and Net Zero, also at the grid operator NESO, as well as the Government’s new Net Zero Mission Control team, the Climate Change Committee, and the energy regulator Ofgem.

To pick apart just some of the most questionable claims:

Energy security

What the Government means by this is that wind and solar are “home-grown” power sources, in contrast to natural gas, an increasing proportion of which has to be imported as the UK’s offshore oil and gas sector declines. Set against that is their intermittency. They are not controllable but swing wildly and only semi-predictably.

Given that the core feature of any electricity grid is that supply and demand must balance exactly for every second of every minute of every hour of every day of the year, relying almost entirely on such variable power sources is exceedingly insecure. In fact it is merely swapping one form of insecurity (exposure to global gas prices) for another (reliance on the weather).

Price spikes

This has been Labour’s and now the Government’s key argument since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, when the powerful slogan: renewables are nine times cheaper than gas first emerged and was briefly true. But the December dunkelflaute shows that it is possible to have even higher price spikes in a heavily renewables’-reliant system, driven not mainly by a high price of gas but by massive shortage of supply.

Thankfully, on this occasion Britain didn’t see the huge increases in power prices that happened on the continent. However, there’s no guarantee that future dunkelflautes won’t have the same impact here.

Reindustrialisation

Far from reindustrialising the country, there is every sign that the Government’s “sprint for clean power” is having the opposite effect. In the narrowest terms, policy-driven investment in grid expansion and subsidy-driven growth in renewable energy and carbon capture projects does create jobs - possibly even thousands in aggregate. But far more jobs are threatened across a wide range of manufacturing and energy-intensive industries due to the high electricity prices that Britain already suffers, and which will worsen under this plan.

“Cheap” renewables

The current Government took power in July 2024 with a promise that, by expanding “cheap” renewables, it would cut £300 per year off the energy bills of every household in Britain. This was a fiction that could only prosper amidst high world gas prices around 2022, and by exploiting public ignorance of how the electricity system works.

Unlike with fossil fuel-based systems like gas, the “fuel” for intermittent renewables, in the form of sun or wind, is essentially free. As a result renewables have relatively much lower marginal costs for every extra kWh of production. This is important for the dynamics of the competitive electricity market. But it does not mean that overall costs of renewables are lower than gas, because renewables have much higher capital costs per MW of installed capacity, and this has to be repaid over their operating lifetimes.

As a result, in Britain all renewables are subsidised, currently through a system called Contracts for Difference. Blogger David Turver, has calculated the average cost of current CfD contracts to be £110/MWh of solar, £113/MWh of onshore wind and £150/MWh of offshore wind. Early rounds of the CfD, as well as previous subsidy schemes, were even more expensive. Even the current CfD averages are all above the current “market reference price”, meaning a net additional cost to electricity consumers.

The CfD is a smart subsidy scheme which pays out only if the price of renewable electricity is higher than the market reference price. Data published by the Low Carbon Contracts Company which was helpfully charted by David Turver here, shows that only during the peak of the Ukraine War gas crisis did operators pay back.

Moreover, renewables come with further costs that are less visible because they don’t show up on bills at all or don’t appear as “cost of energy”. One of these is that when renewables produce more than the grid can handle they can be paid to switch off. So-called “curtailment” fees are currently running at about £1bn per year.

Then there is the cost of grid expansion. Transmitting electricity right around the country doesn’t come cheap, but Britain already has a workable system developed over decades to transport electricity from large power stations to homes and factories. Now, though, the expansion of remote and decentralised renewable generation is demanding a massive upgrade costed at £77.4bn just between 2026 and 2031. This expense, too, must be borne, either by bill-payers or taxpayers.

Nor is this even the end of it. Clean Power 2030 is forced to acknowledge that even if the Government manages to boost renewables so much that there is capacity to produce more than 100% of national demand, there will be times - such as the mid-December dunkelflaute - when gas must still be called on to meet a large part of national demand.

In fact the Government’s official goal is for clean power to meet 95% of demand over any year. This means that more than 20GW of gas generation capacity will have to be kept available even though hardly used. It is far more expensive per MWh to operate sophisticated power stations in this way. As a very interesting recent blog by energy consultant Kathryn Porter also points out, it is also extremely technically challenging. My broader insight, though, is that, once gas is operating as an adjunct, then a large part if not all its costs are actually those of the renewables-based system.

Advocates for renewables point to large falls in the price of renewables as well as battery storage as pointing towards a world in which, even if they were more expensive in the past, renewables (backed by storage) will be cheaper in future. Sadly, for a developed country like the UK this too looks like fantasy.

Due to its latitude and cloudy weather, solar is functionally useless in the depths of the British winter, just when electricity demand is highest. In mid-winter it often produces just a few percentage points of total installed capacity and only for three or four hours during each day.

Grid-scale battery storage is touted as another solution to “balance” the intermittency of renewables. But as LSE professor Luis Garicano pointed out following the December dunkelflaute, even current ambitious European plans for grid-scale storage batteries won’t solve the problem of disappearing wind and sun “for decades”. Moreover, the potentially multi-billion price of installing mass-storage batteries also have to be understood as an additional cost of an electricity system built primarily around renewables.

Finally, and worryingly for the UK given the Government’s enormous plans for expanding offshore wind power, official forecasts of falling costs look like being another fantasy. This has been clear for a while, as documented by Kathryn Porter in 2023. Analyst and campaigner Andrew Montford recently called the difference between official forecasts and reality an “astonishing scale of deception”

Even in the Government’s own rhetoric, the fiction of cheap renewables is starting to unravel. In Clean Power 2030 the Government now claims it is building an energy system that “can bring down energy bills”. Not “will”, but “can”. Elsewhere, it now feels unable to refer to “cheap renewables”, promising instead to “work relentlessly” to “translate the much cheaper wholesale costs of clean power into lower bills for consumers”.

This is mainly a reference to a lively ongoing debate over whether to replace Britain’s single national price for electricity with geographically differentiated prices based on zones or nodes. But while there is certainly scope through this for some consumers to benefit from lower prices at some times, it would not reduce the overall system cost of renewables, which will still have to be paid by someone.

The risks of gas

Launching Clean Power 2030, Ed Miliband says that by pursuing “clean electricity” the Government will “protect working people from the ravages of global energy markets.” He returns to this theme frequently in interviews. But how big is the risk of gas price volatility really?

There’s no doubting that the 2022 gas price spike was enormous and damaging. But if we’re going to re-engineer the entire electricity system in response at a cost of tens of billions of pounds then there should be an honest assessment of both the past record of gas and the likelihood of extraordinary future price spikes. The Government has done neither.

In fact, the recent history of gas prices shows that, the Ukraine War aside, there has been relative stability. Predicting the future is far more hazardous, but there are plausible scenarios in which the 2022 spike could be a one-off: the Ukraine War could soon be over; European port capacity for liquefied natural gas is now much higher; the UK could if it wished boost domestic gas supply and increase underground storage closer to the continental average.

Certainly, if gas prices were to go ballistic again in future it would have serious consequences. However, Ed Miliband effectively misleads the nation by failing to acknowledge that future spikes on the same scale as 2022 are a risk not a certainty.

In fact things are worse than that. It’s not just political sloganeering, but as think tank CPS revealed in November, the GB grid operator’s modelling for grid decarbonisation is based on gas prices being far higher than most market analysts expect.

Reasons to worry

We should worry enormously that the Government’s plans for the electricity system are based on wishful thinking rather than hard analysis because the result will be high energy prices and economic pain, for all “working people”. Indeed, we are already there, with costs to consumers and industry higher than other European countries, and much higher than in America or China. For a start this inevitably drives deindustralisation. More generally, because energy is a key element of costs across the economy, it more or less guarantees economic stagnation. Britain desperately needs lower energy prices - Clean Power 2030 looks very likely to deliver the opposite and we will all suffer.